How does the epithelium contribute to asthma pathology and symptoms?

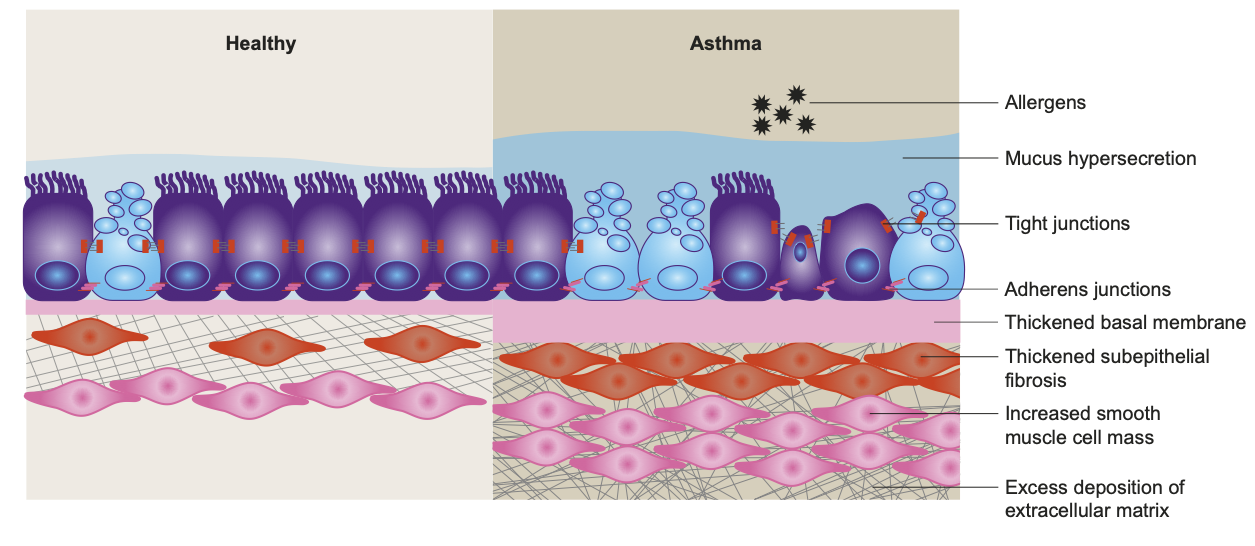

In asthma, as well as marked airway inflammation, there can also be associated structural changes to the airway epithelium (Figure 1), which renders the airways more vulnerable to infection and environmental triggers.2 Both the extent of inflammation and structural changes influence the severity of the disease and asthma symptomatology.3

Structural changes include goblet cell hyperplasia2,3 and, in more severe disease, a change in mucin expression, primarily increase in the MUC5AC to MUC5B ratio, results in an MUC5AC-rich gel that tethers to epithelial mucous cells and markedly impairs mucociliary transport.13 This increase in submucosal goblet cells and mucus plugging leads to airway blockage.3,13

There is also a decrease in the number and integrity of tight junctions,1,3 leading to tissue damage as external triggers are able to penetrate the airway wall.

Increased epithelial thickness2,6 and subepithelial fibrosis6 have also been observed, resulting in airway narrowing and fixed airway obstruction, respectively.

Finally, there are increased levels of inflammatory cells (including mast cells and eosinophils),14,15 which, in turn, cause heightened inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness.